KAWARAMACHI, Japan – Nestled on the southwestern island of Shikoku, time seems to stand still in the small village of Kawaramachi. Here, women gather in a quiet circle, their hands meticulously stitching intricate patterns onto small balls the size of an orange. This is the art of Sanuki Kagari Temari, a Japanese tradition that has been passed down for over 1,000 years.

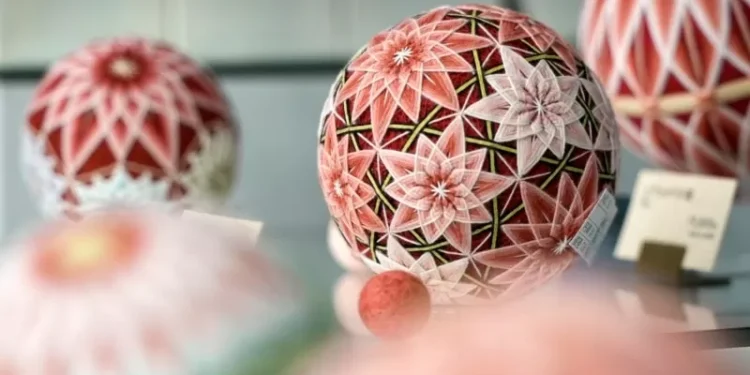

At the center of the circle is Eiko Araki, a master of the craft. Each temari ball is a masterpiece, adorned with colorful geometric patterns and given poetic names like “firefly flowers” and “layered stars”. It takes weeks, even months, to complete a single ball. Some can cost hundreds of dollars, while others are more affordable.

These kaleidoscopic balls are not meant for throwing or kicking around. They are treasured as heirlooms, carrying prayers for health and goodness. In Western homes, they may be cherished like a painting or sculpture.

The concept behind temari is one of elegant otherworldliness, a beauty that is both impractical and labor-intensive to create. “Out of nothing, something this beautiful is born, bringing joy,” says Araki. “I want people to remember that there are beautiful things in this world that can only be made by hand.”

The use of natural materials is an essential part of the temari tradition. The region where it originated was known for its cotton production, and even today, the balls are made from this humble material. At Araki’s studio, which also serves as the head office for temari’s preservation society, there are 140 shades of cotton thread, ranging from delicate pinks and blues to vivid colors and subtle gradations in between.

The women at the studio dye the thread by hand, using plants, flowers, and other natural ingredients. Cochineal, a bug found in cacti that produces a red dye, is used to create a deep shade of red. Indigo is repeatedly dyed to achieve a nearly black color, while yellow and blue are combined to create beautiful shades of green. To deepen the colors, a dash of soy juice and organic protein is added.

Outside the studio, loops of cotton thread in various shades of yellow hang outside to dry in the shade. The process of creating and embroidering the balls is a laborious one. It begins with making a basic ball mold using rice husks that are cooked and dried before being wrapped in cotton and wound with thread until a ball is formed.

The stitching process is equally challenging. The balls are surprisingly hard, and each stitch requires a concentrated and precise push. The motifs must be exact and evenly stitched. Each ball has guiding lines, one that goes around it like the equator, and others that zigzag to the top and bottom.

In recent years, temari has gained recognition among both Japanese and foreigners. Even Caroline Kennedy, former United States ambassador to Japan, took lessons in ball-making during her time in the country. Yoshie Nakamura, who promotes Japanese handcrafted art in her duty-free shop at Tokyo’s Haneda airport, features temari because of its intricate and delicate designs. “Temari, which may have been an everyday item in a different era, is now being used for interior decoration,” she says. “Each Sanuki Kagari Temari is a unique and special work of art.”

Araki has also been working on modernizing the art form while still preserving its traditional roots. She has created new designs that appeal to a younger generation and are more accessible for everyday use. For example, temari balls can now be used as Christmas tree ornaments. She has also designed small, affordable straps with dangling miniature balls, perfect for everyday use or as gifts.

One of Araki’s most innovative creations is a cluster of pastel balls that can be opened and closed using tiny magnets. These can be filled with sweet-smelling herbs, creating a unique and aromatic diffuser.

The tradition of temari has been passed down through generations, but it is not without its challenges. Araki admits that the most difficult aspect is finding and nurturing successors. It takes over 10 years to train someone to make temari to traditional standards, so dedication and passion are essential qualities for anyone looking to continue the craft. However, for those who find joy in the process, the rewards are immeasurable.

Araki’s in-laws, who were temari